Calling Each Other Out and Calling Each Other In: The Grit & Grace of Accountability

“We’re good at calling each other out. But can we call each other in?” That was the question someone posed in a recent webinar I attended on the #metoo movement.

On that webinar, I heard wonderful men of all races and ages say that they genuinely want to become more aware and skillful in gender relations, but they withdraw because it feels too dangerous. I also heard women who want to express support for men, but stay silent to avoid being excommunicated for being anti-feminist. And I heard women who are just so frustrated that they read men the riot act or walk away in peeved silence.

How can we bridge this gap if we’re hiding in our corners or taking each other’s heads off?

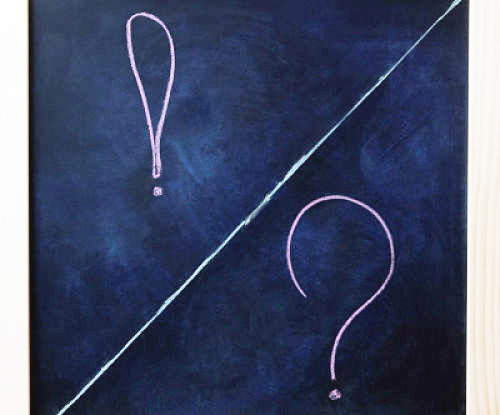

We long for a higher standard in our behavior toward each other, and I think there’s something healthy and hopeful about this new call to accountability. But our way of holding each other to that higher standard is so limited. Calling each other out – through shame and blame – seems to be our grit-laced go-to for accountability.

Don’t get me wrong. There are many situations where unequivocal public call-outs and fierce corrections are the right response. Harvey Weinstein (who is being arraigned as I write this) and Matt Lauer come to mind. These aren’t well-intentioned guys who are fumbling to get it right. They are drunk on power and heedless of the pain they cause. And while these are very public figures, we’ve known (or known of) those guys in our own lives. Behavior like theirs should be met with righteous grit: unambiguous line-drawing, public outcry, and no-kidding consequences. The act of “calling out” belongs here and I’m all for it.

Don’t get me wrong. There are many situations where unequivocal public call-outs and fierce corrections are the right response. Harvey Weinstein (who is being arraigned as I write this) and Matt Lauer come to mind. These aren’t well-intentioned guys who are fumbling to get it right. They are drunk on power and heedless of the pain they cause. And while these are very public figures, we’ve known (or known of) those guys in our own lives. Behavior like theirs should be met with righteous grit: unambiguous line-drawing, public outcry, and no-kidding consequences. The act of “calling out” belongs here and I’m all for it.

But as author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie says, “There is a difference between malice and a mistake.” Much of the sexist behavior I’ve encountered hasn’t come from a malicious dominating intent, but rather from a lack of inner and outer awareness. I’m going to call this ‘garden variety’ sexism. You know: the offhand remark, the interruptions and mansplaining, the feedback about your ‘tone’ (that your male counterparts never receive).

When we encounter garden-variety sexism, we have a choice to make. Do we call him out, pushing him into the cold light of blame, or do we call him in to a deeper conversation? A lot depends on the context, and those options are the opposite poles in a much wider range of responses.

Calling each other in is for situations where decent but flawed people mess up, and where we see (or hope) that a more respectful relationship is possible.

But what does “calling someone in“ even mean? What does it look like?

But what does “calling someone in“ even mean? What does it look like?

- It means speaking up on behalf of a stronger relationship, not from a place of blame.

- It means asking for permission to confront. “Bill, you said something in that meeting yesterday that’s still not sitting right with me. Would you be willing to talk it over?” It’s a simple and powerful alignment move that we often overlook.

- It means preparing for the conversation about intent vs. impact. What’s tricky about garden-variety ‘ism’ behavior is that it’s often done unconsciously and without intent. But a lack of intent doesn’t erase the impact. Talking this distinction through can be a real opportunity for two people to understand each other and true up their actions.

- It means being humble, knowing that most of us have injured or marginalized someone who was different from us. I may have a legitimate sexist beef with you, but as someone who is white, straight and cis-gendered, I have to remember that I’ve got no high horse to sit on.

- It also means keeping it real. Calling someone in doesn’t require you to swathe your message in hearts and flowers. Be factual about what happened. Be clear about how it affected you. And after you’ve heard each other out, be specific about what you want to happen differently going forward.

What about you?

Think of a time when you said or did something that someone else experienced as hurtful or demeaning. How would you have wanted him or her to address that with you?

Can you recall sexist situations in which you responded either more wimpily or fiercely than the situation required? What did you learn from that?

How do you make the distinction between when to call someone out and when to call him in?

What does each mode invite you to attend to, summon, or manage in yourself?

Interested in developing your own or your team’s capacity in this area? Contact me today!

Thanks for another great posting Leslie. What I like about this distinction is that it removes what has felt to me like a false binary between staying in relationship and focusing on accountability of one’s actions. In some recent local and highly publicized incidents of racist behavior, what was clear to me is that there is not much dignity for anyone in outcomes that lead to hardcore shaming and court of public appeal accounting for racist or other kinds of discriminatory behavior. I have been left looking for what is possible in creating a learning space to improve understanding and future behavior for everyone touched by sexist or other demeaning behaviors. Your posting reminds me that it is not simply about a lack of information, it is also a scarcity of feeling what impacts others and a re-membering of how what I say or do is connected to others. I am feeling called lately to counter freedom of speech and freedom of individuals generally with a counter move to say publicly, I feel free to care deeply about how we are in community and I want to invite you to care too in how you show up in it. Thanks for a thoughtful offering on this area.

Cheryl, I love how you’re engaging in this issue! Communicating authentically and respectfully across the divide seems to be one of our culture’s pressing “development edges.”